Rare, threatened subspecies of dolphins and porpoises live in the Black Sea along Ukraine’s coast. They are also victims of war, along with the researchers who study them.

Last year, I worked closely with 20 scientists including both Ukrainian and Russian colleagues to identify dolphin and porpoise habitats in the Black Sea. Following our five-day scientific workshop, we were celebrating as I posted news stories announcing the identification of what we call ‘Important Marine Mammal Areas’, or IMMAs, around the Black Sea, including six areas bordering Ukraine.

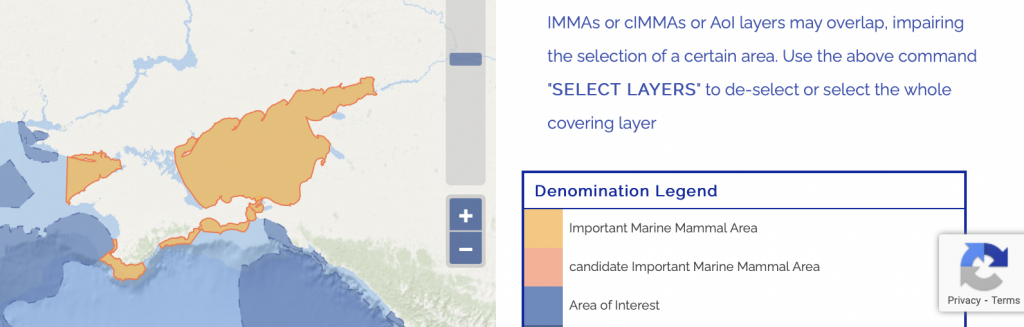

IMMAs are areas of ocean identified by scientists as having special importance for marine mammals. They could be where whales, dolphins or porpoises come to feed or maybe to breed and raise their young. They might be migratory routes or where whales or dolphins congregate for any number of different reasons.

Identifying these areas as IMMAs is a vital first stage in getting habitats protected, and that’s just what we were celebrating having done in the Black Sea. Then came Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. These IMMAs are now threatened along with the three porpoise and dolphin subspecies already on the IUCN RedList: the endangered Black Sea harbour porpoise and Black Sea bottlenose dolphin, and the vulnerable Black Sea common dolphin.

Over the past two months, our IMMAs have been subjected to extensive military traffic including at least 20 Russian warships, exploding missiles and bombs, fires, ship sinkings, and the placing of floating mines. The human tragedies in Ukraine are at the forefront of our concerns, yet these tragedies extend also to nature and wildlife on land and in the waters off Ukraine.

The Black Sea common and bottlenose dolphins and the Black Sea harbour porpoise are found in the Karkinit and Dzharylhach (Carılğaç) Gulfs IMMA separating the northwestern Crimean Peninsula from the Ukrainian mainland (where Kherson is located). On the eastern side of Crimea, the Kerch Strait and Taman Bay IMMA, which is at the entrance to the Sea of Azov IMMA, hosts massive early spring anchovy and other fish migrations that harbour porpoises and bottlenose dolphins follow and feed on. This is a major entry point for the ships involved in offensives in southeast Ukraine including the besieged and now devastated Mariupol. The Sea of Azov IMMA itself has a unique form, a distinct population of the subspecies of harbour porpoise, distinct even from the rest of the Black Sea population. It has been reported in recent days that some of these IMMAs along the occupied Ukrainian coast are full of floating Russian naval mines, deployed somewhere in the area between Sevastopol, Odesa and Snake Island. And even on the other side of the Black Sea, 300 to 400 miles (500-650 km) away, the Tudav research team from Turkey have been encountering floating mines. These mines will make research as well as transport, fishing and tourism in the Black Sea much more dangerous for years to come.

In recent weeks, we’ve been getting reports from researchers we’ve worked with telling us about record numbers of dead dolphins and porpoises washing up along the coast of western Turkey as well as Romania. While some of these may be natural deaths, the large number implicates the war as a cause. This includes, for western Turkey, more than 80 common dolphins, according to Tudav, with no signs of entanglement or gunshot wounds. In Bulgaria, more than 50 porpoises have died in nets, far more than is usual for this time of year. The military activities, including the noise from explosives and low frequency sonar, may be killing some dolphins and porpoises and driving others south to Bulgarian and Turkish shores, where they are stranding or getting caught in fishing nets.

Dolphins and porpoises use echolocation to find their food and navigate; their hearing is acute yet sensitive to noise levels. Sounds from the firing of missiles, explosions and sonar from ships can carry for many miles underwater, potentially disturbing, killing or driving away dolphins and porpoises. Thus, these important habitats that we had earmarked for protection as marine protected areas are now being devastated with the dolphins and porpoises being killed or pushed out.

We also have reports that so called ‘combat dolphins’, trained by the Russian military in Crimea, may be being used to monitor the Russian-controlled port of Sevastopol where the Russian fleet, reportedly fearful of being sunk, has retreated. Two dolphin pens have shown up on recent MAXAR satellite pictures at the entrance to Sevastopol harbour. Attempted military use of dolphins is not new and goes back to the US Navy experiments beginning in the early 1950s and then in Vietnam in the 1960s and later in the Persian Gulf, in the latter case to search for mines.

Almost 18 years ago, in 2004, I visited Crimea and toured one of the broken down facilities where dolphins were kept. When Putin invaded Crimea in 2014, he assumed control over the dolphin aquariums there with bottlenose dolphins then being shipped to Russia, and since then more have been captured in the Black Sea off Crimea. The Russian combat dolphins, based in Sevastopol, are said to be trained to search for and tag underwater mines or identify unwanted swimmers attempting to access restricted waterways, according to National Geographic quoting RIA Novosti, as its source.

Ukrainian dolphin scientist Pavel Gol’din, however, doubts that dolphins are being used as underwater saboteurs when robotic devices are now the norm for secret attack as well as potential detection. There is no doubt that many cruel and deadly experiments with dolphins have been tried in the past by the US and Russian Navy, but, says Dr. Gol’din, ‘there is no evidence that dolphins have been successfully employed in combat duty. Although dolphins are good at finding fish buried in sand using echolocation, there is no solid evidence that they ever successfully found mines. Instead, what’s happening with these dolphins in Sevastopol is that they are being exposed to damaging Russian Naval sonar.’

I think the full impact to these three Black Sea threatened subspecies of dolphins and porpoises will only come after the war. Dodging the mines, researchers will have their hands full trying to assess the wider damage to the coastal ecosystem. For the six IMMAs along the coast of Ukraine, the prospects are poor. For now, we can say little except that this huge human tragedy includes our dolphin and porpoise friends as well, and the scientists and conservationists who care about them. They are all in this together, with long-term impacts on all our lives.